Updated on:

Indoor allergens can make home feel like a safe haven—until your nose, eyes, or lungs disagree. Because we spend so much time indoors, small exposures (dust mites in bedding, mold in damp corners, pet dander in upholstery) can add up. Here we explain what indoor allergens are, how to spot them, and how to lower your exposure with practical steps grounded in trusted public health sources.

What are indoor allergens?

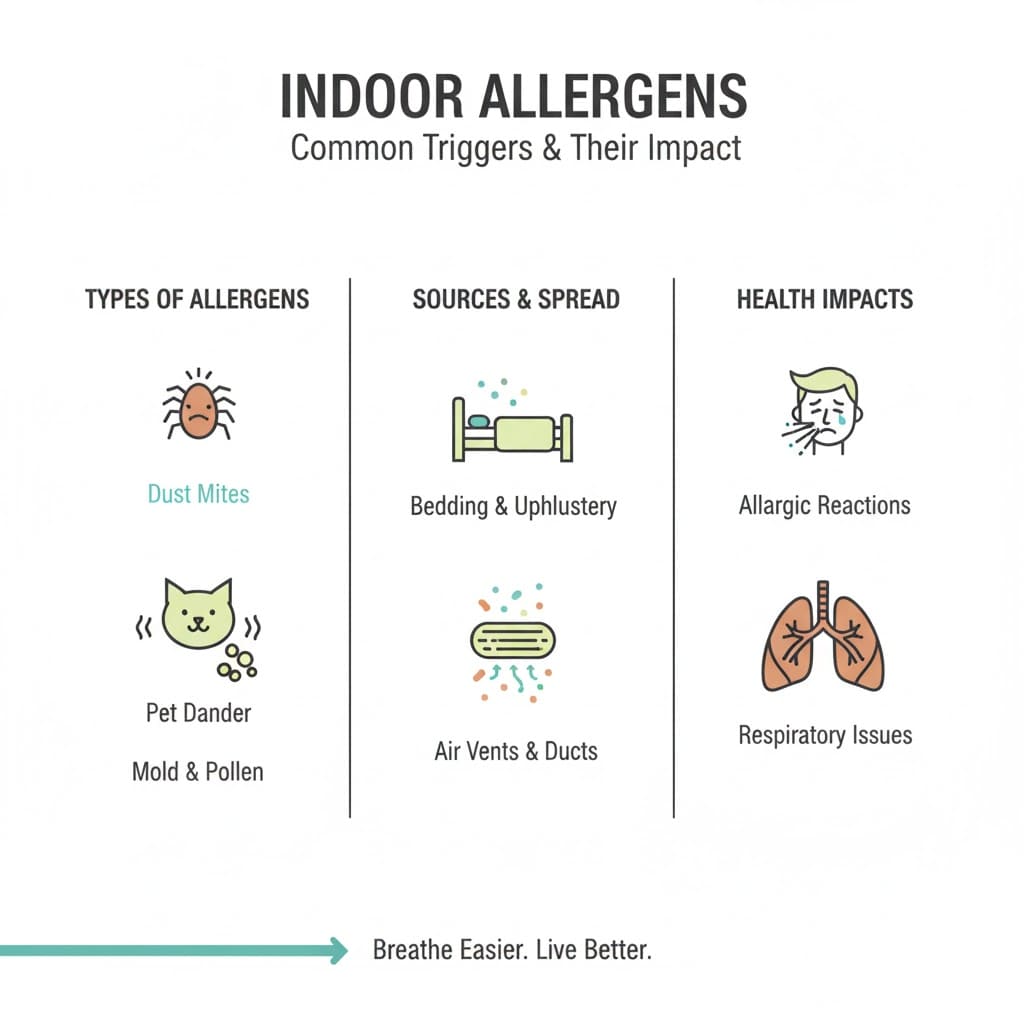

Indoor allergens are substances found inside buildings that can trigger an immune reaction in people who are sensitized. They are often biological in origin (like dust mites, mold, and animal dander) and may be invisible until symptoms show up.

Public health agencies commonly group indoor allergen sources with other biological pollutants because they travel on tiny particles and can accumulate in dust. Common biological contaminants listed by the U.S. EPA include animal dander, house dust and mites, cockroaches, pollen, and molds.

Important nuance: not every indoor irritant is an allergen. For example, smoke, fragrances, or cleaning chemicals can worsen symptoms without causing an allergy, especially in people with asthma or sensitive airways.

What are the most common types of indoor allergens?

In most homes, the big five indoor allergens are dust mites, pet dander, mold spores, cockroach allergens, and rodent allergens. Pollen can also become an indoor problem when it enters through doors, windows, and clothing.

Here’s what they are, where they hide, and why they matter:

- Dust mites: Microscopic relatives of spiders that live in bedding, mattresses, upholstered furniture, and carpets. Dust mite allergens are among the most common worldwide.

- Pet dander: Tiny flakes of skin plus proteins from saliva and urine that cling to fabric and stay airborne when disturbed.

- Mold: Fungal growth that releases spores and fragments; often tied to dampness, leaks, and poorly ventilated bathrooms or basements.

- Cockroach allergens: Proteins from droppings and body parts; more common where food residues and moisture are available.

- Rodents: Allergens from urine, dander, and saliva; can become airborne in dusty areas.

What are the symptoms of indoor allergen exposure?

Indoor allergen exposure most often causes allergic rhinitis (sneezing, runny or blocked nose, itchy eyes) and can trigger asthma symptoms in susceptible people. Symptoms often worsen after cleaning, making the bed, being around pets, or spending time in damp areas. (AAFA

Common symptom patterns include:

- Sneezing, nasal congestion, runny nose

- Itchy, watery eyes; itchy nose or throat

- Coughing, chest tightness, wheezing (especially in asthma)

- Skin irritation or eczema flare-ups in some people

If you have shortness of breath, severe wheezing, facial swelling, or symptoms that rapidly worsen, seek urgent medical care.

How do I tell the difference between indoor allergies and a cold?

Allergies are an immune reaction to a trigger, while colds are viral infections. A helpful rule: allergies often cause itching and persist as long as the exposure continues, while colds tend to resolve within about a week or two.

Clues that point more toward allergies:

- Itchy eyes or nose are prominent.

- Symptoms start quickly after exposure (e.g., cleaning, pets, entering a musty room).

- No fever; symptoms persist or recur in the same indoor settings

Clues that point more toward a cold:

- Sore throat, fever, or body aches

- Symptoms evolve over a few days and then improve

- Close contacts are sick, too.

How do you tell if your house is giving you allergies?

If symptoms reliably improve when you leave home and return when you come back, your indoor environment is a strong suspect. Look for dampness, visible mold, pest activity, and dust reservoirs (bedding, carpets, soft furniture) and consider tracking symptoms alongside simple indoor measurements.

A practical, low-tech checklist:

- Dampness: leaks, condensation on windows, musty odors, water stains

- Dust reservoirs: carpets, heavy curtains, upholstered furniture, clutter

- Pets: sleeping on beds/sofas, shedding, litter boxes or pet bedding indoors

- Pests: droppings, food crumbs, gaps around plumbing or baseboards

If you want data (without turning your home into a lab), a humidity meter and a CO2 monitor can be useful. CO2 itself is not an allergen, but it can hint at ventilation patterns - and ventilation affects how pollutants and particles build up indoors.

How can I reduce dust mites in my bedroom?

Bedrooms are prime dust-mite territory because mites feed on shed skin and thrive in soft, warm materials like mattresses and pillows. The most effective approach is to reduce their habitat (bedding and fabrics) and keep humidity low.

High-impact steps (start here):

- Wash sheets, pillowcases, and washable bedding weekly in hot water—about 130°F / 54°C—and dry thoroughly.

- Use allergen-proof encasements on pillows and mattresses.

- Keep indoor relative humidity around 30% to 50% when possible; mites struggle as humidity drops below ~50%.

- Vacuum floors with a well-maintained vacuum; if you’re very sensitive, consider a HEPA-equipped vacuum and have someone else vacuum when possible.

Evidence notes: Hot-water washing at about 130°F/54°C weekly is commonly recommended in clinical guidance for dust-mite control.

Dust mites require relatively high humidity to thrive; survival and proliferation drop as humidity decreases below about 50%.

How does indoor humidity affect mold and allergen levels?

Humidity is the volume knob for many indoor allergens: higher moisture supports mold growth and helps dust mites survive. Keeping indoor relative humidity in a moderate range can reduce biological growth and allergen buildup.

The U.S. EPA notes that a relative humidity of about 30% to 50% is generally recommended for homes, and its mold guidance advises keeping humidity below 60% (ideally 30% to 50%) to discourage mold and pests.

Practical humidity tips:

- Fix leaks and dry water damage promptly (mold follows moisture, not your calendar).

- Use bathroom and kitchen exhaust fans and vent dryers outdoors.

- In damp climates or basements, consider a dehumidifier and empty/clean it regularly.

- If indoor air is very dry, humidify carefully—over-humidifying can worsen mold and mites.

Do air purifiers actually remove indoor allergens?

Yes—for airborne particles. A properly sized air purifier can reduce allergen particles suspended in the air, especially when it uses a high-efficiency filter and runs consistently. But air cleaning works best alongside source control (cleaning, moisture control, pest management) because allergens also live in dust and fabrics.

The EPA explains that portable air cleaners often achieve high performance for particle filtration by using HEPA filters and recommends selecting a unit with a Clean Air Delivery Rate (CADR) appropriate for your room size.

Quick shopping/usage checklist:

- Choose a unit intended for particles (HEPA or equivalent) and sized for the room (check CADR/room coverage).

- Run it where you sleep or spend the most time; keep doors/windows behavior consistent with your goal.

- Replace filters on schedule; a clogged filter is like a tired bouncer at a club.

- For odors and some gases, you need an adsorbent media (often activated carbon); HEPA alone is for particles.

HEPA is officially defined in the U.S. (via the Department of Energy definition cited by the EPA) as filtration that can capture at least 99.97% of airborne particles sized 0.3 microns in a test context.

What is the best way to remove pet dander from a home?

The most effective strategy is to reduce how much dander builds up in the first place, then remove what settles into fabrics and dust. Because pet allergen proteins can cling to surfaces, consistent cleaning routines matter more than occasional deep cleans.

Steps that tend to help most:

- Keep pets out of the bedroom and off bedding to protect your highest-exposure zone (sleep).

- Wash pet bedding and soft throws regularly; vacuum upholstered areas.

- Use a HEPA air cleaner in rooms where the pet spends time (and where you do).

- Damp-dust hard surfaces (dry dusting can re-aerosolize particles).

Are indoor allergens worse in the winter or summer?

It depends on the allergen and your building. Many people notice worse indoor symptoms in winter because homes are closed up and ventilation often drops, allowing indoor pollutants and particles to build up. In humid summers, mold and dust mites may thrive if indoor moisture isn’t controlled.

The EPA notes that in winter, occupants often close windows and increase heating, which can reduce ventilation and cause some indoor pollutant levels to accumulate.

Which flooring is best for people with indoor allergies?

Hard, easy-to-clean flooring can reduce places where allergen-containing dust accumulates, especially in bedrooms. Carpets can hold dust and allergens and can also be harder to clean thoroughly, particularly after dampness or spills.

If you can’t or don’t want to remove carpet, focus on:

- HEPA vacuuming and regular maintenance

- Keeping humidity in a controlled range (to reduce mites and mold)

- Avoiding wall-to-wall carpet in damp-prone areas (basements, bathrooms)

How often should I deep clean to eliminate allergens?

There isn’t one magic schedule, but consistency beats intensity. Weekly routines (bedding laundry, vacuuming, damp dusting) usually reduce allergen load more reliably than rare, all-day cleaning marathons.

A practical cadence many clinicians and public health guides align on:

- Weekly: wash bedding; vacuum main living areas and bedroom; damp dust surfaces.

- Monthly: wash curtains/throws (if washable); clean HVAC return grilles; inspect for dampness.

- Seasonally: check under sinks and around windows; clean/replace HVAC filters as recommended; address any moisture issues.

How can CO₂ levels and ventilation affect indoor allergens?

Ventilation dilutes indoor pollutants and particles. If ventilation is low, allergens and irritants can linger longer and concentrate in occupied rooms.

CO₂ monitoring can help you understand ventilation patterns because indoor CO₂ rises with people and falls with fresh-air exchange. The EPA cautions that CO2 needs careful interpretation, and CDC/NIOSH suggests that (for some space types) baseline readings below about 800 ppm can represent good ventilation—but no single number fits every room or occupancy.

If you see consistently high CO₂ while occupied, consider opening windows (when outdoor air is cleaner), increasing mechanical ventilation, or running the HVAC fan with an appropriate filter—and keep humidity under control.

What are the 14 major allergens?

This question usually refers to the 14 allergens that must be declared on food labels under EU rules—not indoor air allergens. They include gluten-containing cereals, crustaceans, eggs, fish, peanuts, soybeans, milk, nuts, celery, mustard, sesame, sulfur dioxide/sulfites, lupin, and mollusks.

If you meant “major indoor allergens,” the most common household triggers are dust mites, mold, pet dander, cockroach allergens, and rodents.

Can allergies cause tingling?

Sometimes. A specific example is Oral Allergy Syndrome (pollen-food syndrome), where certain raw fruits, vegetables, or nuts can cause itching or tingling of the lips, mouth, or throat shortly after eating.

Tingling can also have many non-allergy causes. If tingling is severe, involves swelling, breathing difficulty, or systemic symptoms, seek urgent medical care.

Conclusion: a calmer, cleaner plan for indoor allergens

Indoor allergens are manageable—not by chasing perfection, but by steadily lowering exposure where it matters most. Start with the bedroom (bedding, humidity), then address moisture, dust reservoirs, and ventilation. If symptoms persist, an allergist can help confirm triggers and tailor a plan so you’re not guessing.

Actionable takeaways:

- Keep humidity in a moderate range (often around 30% to 50%) and fix moisture problems fast.

- Wash bedding weekly (hot water is important for dust-mite control) and use allergen encasements if needed.

- Use a properly sized HEPA air purifier for particle allergens—and pair it with cleaning and moisture control.

- Improve ventilation when conditions allow; use CO2 trends as a clue, not a verdict.

FAQ about indoor allergens

What are the most common indoor allergens?

Dust mites, pet dander, mold, cockroach allergens, and rodent allergens are among the most common indoor triggers; pollen can also be tracked indoors via clothing and airflow.

How do I tell the difference between indoor allergies and a cold?

Allergies often cause itching and persist with exposure, while colds are viral, may cause fever/body aches, and typically resolve within 7-14 days.

What are the symptoms of indoor allergen exposure?

Sneezing, congestion, itchy/watery eyes, and cough are common; in asthma, allergens may trigger wheezing or chest tightness.

How can I reduce dust mites in my bedroom?

Wash bedding weekly in hot water (~130°F/54°C), use allergen encasements, and keep humidity low enough that mites struggle (often below ~50%).

Do air purifiers actually remove indoor allergens?

They can reduce airborne allergen particles, especially with HEPA filtration and correct room sizing, but they don’t replace cleaning and moisture control.

How does indoor humidity affect mold and allergen levels?

Higher humidity encourages mold growth and dust-mite survival; moderate humidity (often 30-50%) helps limit biological growth.

What is the best way to remove pet dander from a home?

Limit pet access to bedrooms, clean fabrics and surfaces regularly, and use HEPA filtration in key rooms for airborne particles.

Are indoor allergens worse in the winter or summer?

Winter can worsen exposure when ventilation drops; summer can worsen mold and mites if humidity rises and dampness isn’t controlled.

Which flooring is best for people with indoor allergies?

Hard, cleanable floors tend to reduce dust reservoirs compared with wall-to-wall carpet, especially in bedrooms.

How often should I deep clean to eliminate allergens?

Weekly routines (bedding wash, vacuuming, damp dusting) usually matter more than occasional deep cleans; adjust based on symptoms and pets.